Art from Guantánamo Bay

Baron & Ellin Gordon Art Galleries’ Spring Exhibition

This article first appeared in the spring 2022 Mace & Crown magazine issue.

The Baron & Ellin Gordon Art Galleries’ spring exhibition, “Art from Guantánamo Bay,” featured the artwork of six detainees who were held at the Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp without formal charges.

The work of Moath Al Alwi and Ahmed Rabbani – both current detainees – appeared alongside that of Muhammad Ansi, Abdualmalik Alrahabi Abud, Sabri Al Qurashi, and Mansoor Adayfi, all of whom spent more than a decade in confinement. On display from January until May, the exhibit served to educate ODU students, faculty and the greater Hampton Roads community on the gruesome human rights violations occurring at Guantánamo Bay within the last two decades.

“I felt it was a fitting choice for our educational gallery,” said Dr. Cullen Strawn, executive director for the arts and director of the Gordon Art Galleries. “Throughout ODU we study most aspects of humanity, and the phenomenon of Guantánamo Bay and its detainees are unique while relating to sociology and criminal justice, artistic expression, and other important topics.”

The Guantánamo Bay Detention Camp is a United States military prison located off the coast of Cuba that opened in January 2002, only four months after 9/11. According to the New York Times, approximately 780 detainees have passed through ever since, 702 having been transferred out, 30 passing away after their transfer, and nine having died while at Guantánamo. Today, 39 detainees remain, 18 of whom are currently held in law-of-war detention, meaning they remain uncharged without access to counsel.

According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, “The United States justifies the indeterminate detention of the men held at Guantánamo Bay and the denial of their right to challenge the legality of the deprivation of liberty by classifying them as ‘enemy combatants.’” In other words, 18 people have been stripped of the right to challenge their treatment by U.S. forces – and have subsequently lost all personal liberties – on the grounds that human rights do not apply to accused terrorists, including those who have not been charged as such.

As of 2022, both Al Alwi and Rabbani have been cleared for release, though it may take years to be placed in host countries.

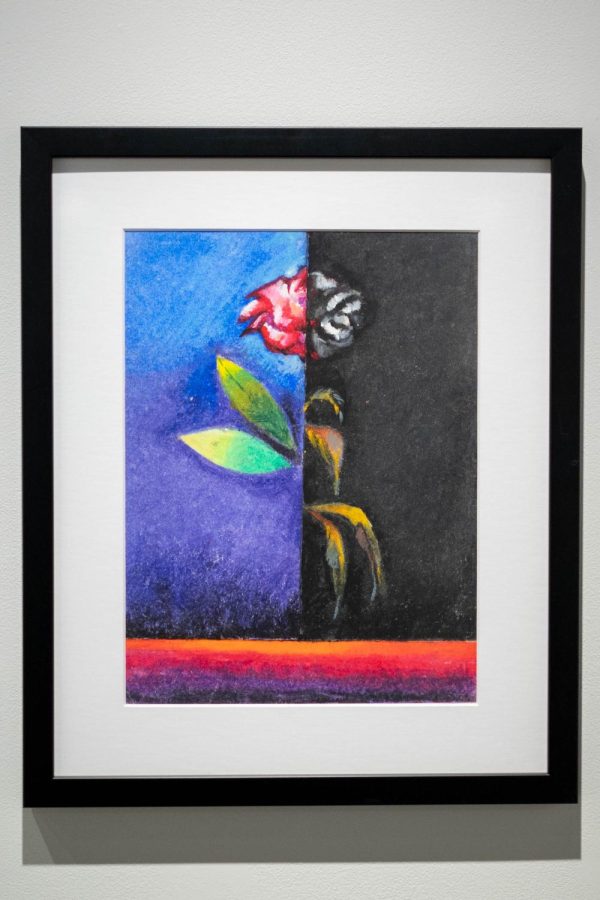

“Art from Guantánamo Bay” displayed 101 of the detainees’ most evocative works, each a living testament to the fraught conditions they were subjected to. Panels with various theme descriptions dotted the walls of the exhibition, identifying notable motifs such as protest, memories and visions, the American Dream, and even music. But nature was by far the most prominent, as flowers, seascapes, fruits and sunsets packed the room with explosive color, often produced with oil pastels or acrylic paint on standard sheets of paper.

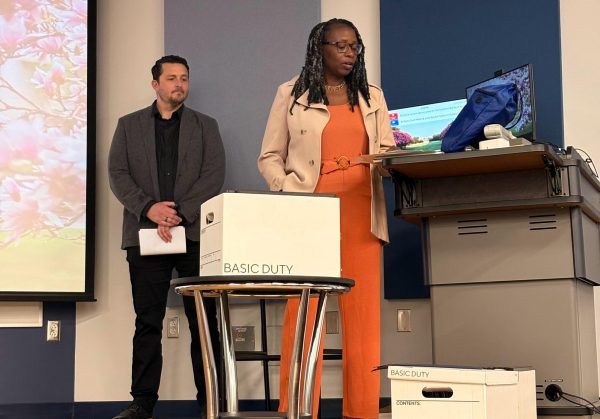

The reception, held on Jan. 27, attracted a diverse audience of admirers who braved the bitter cold to celebrate the opening and meet the evening’s guest of honor, former detainee and artist Mansoor Adayfi. Perusing the gallery on “Gordon,” a telepresence robot allowing for visitors to view the galleries from anywhere around the globe, Adayfi basked in his ability to speak openly about his experiences and artwork.

During ODU’s 44th annual Literary Festival, an excerpt read aloud from Adayfi’s memoir, titled “Don’t Forget Us Here,” revealed that he was falsely accused of being an Egyptian Al-Qaeda leader after warlords ambushed and sold him to U.S. forces in northern Afghanistan. The large sum of reward money offered by Americans at the time – in the wake of 9/11 – routinely prompted such behavior. In return, Adayfi spent 14 years at Guantánamo Bay, uncharged and continually tortured. Today, he is still unable to return home to Yemen.

“You know, when I see people view our art, I feel heavy,” revealed Adayfi. He wore an energetic orange scarf that juxtaposed his inviting, calm demeanor. “I can see the appreciation of the art, and I also see how powerful it is. When I look at it from a writer’s perspective, it’s kind of like a language. This is how the soul communicates – soul to soul. You don’t have to meet the person [viewing your art], maybe you’ll never meet that person, but you can still speak to them – to their soul – through the art. It is not just colors and strokes, no, it is emotions, it is secrets, and it can freeze time and memories.”

Dr. Lee Slater, master lecturer of world cultural studies and director of the world cultural studies program at ODU, prompted her students to attend the reception as a means to engage with the uncomfortable topic of prolonged detention and torture.

“This was an amazing opportunity for students to physically move through the space of storytelling,” said Slater. “As they paused before each drawing, painting, or sculpture, and even while engaging with the more interactive elements, I could see them paying attention to the gaps: the physical space that separated them from the creation of the art, as well as the leagues of [understanding] between the artwork and visitor…Exhibitions like this one have a lasting impact on students and professors alike as we commit to engaging the relationships between global challenges and human communities.”

Perhaps the most ornate pieces in the exhibition were Moath Al Alwi’s model ships, constructed with found objects like cardboard, clothing fabric, prayer caps, beads, wooden meat skewers and soap. In a gut-wrenching anecdote, Strawn revealed that Al Alwi spent the time crafting his ships as a way to imagine himself out at sea, free from the brutal confines of Guantánamo. Strawn continued, “The sea features very prominently [throughout the exhibition]–It is near detainees and gives them hope, but they cannot reach it.”

Several guests flocked to Al Alwi’s ships – perfectly situated beneath protective glass cases – while visiting the gallery, including one of Slater’s students, Katelyn Minor.

“Realizing how old I was when some of this started has really been impactful for me,” Minor contemplated, gazing down at Al Alwi’s work. “This started in 2002, and I was born in 1999. To see this work created by people who have been detained for almost my entire life, experiencing such atrocities… it’s terrifying, and enlightening, and it puts me at a loss for words.”

After five long years of working to bring “Art from Guantánamo Bay” to ODU, Strawn successfully opened the exhibition just 16 days after the detention camp’s 20th anniversary. Though over 100 pieces are featured in the show, many of the detainees’ works were destroyed before attorneys could transport them out, as each must be stamped with approval from the U.S. government prior to being released. Because of such sanctions, each piece seemed to bring with it an air of distinction and posed the question: did the artists ever believe their work would leave Guantánamo Bay? Perhaps not, in which case the ability for students to gaze upon it was, inherently, a privilege.

As Slater insightfully conveyed, “I think that in the end, students will leave this exhibit with both an understanding of the need for the fullness of representation, and with individual moments of connection that they will always carry with them.”

Dana Chesser (She/Her) is an English/Journalism major and second-semester writer for the Mace & Crown. Alongside her role as A&E Editor, she works...

Elena Harris is a speech pathology major and photography minor graduating in the spring of 2023. Outside of the Mace and Crown, Elena enjoys the ODU experience...