Upheaval

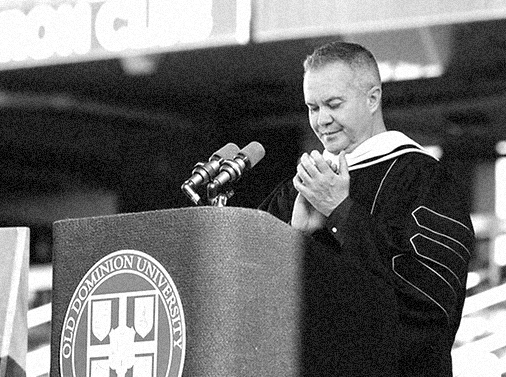

Old Dominion University’s Vice President Dr. Don Stansberry Navigates Leadership in a Post-Lockdown Era

Don Stansberry’s office smells like sweet spices and baked goods.

The scent—emanating from a small diffuser on his desk—is notably named “Fireside.” While he proudly explains that it was a Christmas gift from his niece, I imagine a fireplace in the corner of the room, narrating our conversation with faint pops of wood. It would protrude from the opposite wall of his large, Jacobean-stained bookshelf, characteristically decorated with old photos and rainbow knick-knacks. The eclectic charm of his décor paired with a crackling hearth would exude the familiar comforts of my childhood living room, but the scent alone is almost as inviting, and it brings me back to reality.

As I cross through the aromatic threshold, he tells me to sit anywhere and gestures to the entirety of the room. At least ten chairs populate the office, and a nervous laugh escapes as I momentarily ponder where to go. Though a conference table occupies the wall where my imaginary fireplace would be, I settle for a cushioned seat in front of his desk and cross my legs to mirror his own. He’s allocated nearly an hour of his Monday to our interview—one that was nearly cut short by a call from the university president—and it wouldn’t feel courteous to make him move. But I don’t take his politeness for granted. He could be aloof if he wanted; his position certainly allows for it.

Stansberry has never been one to let his role of vice president overshadow his genuine interest in caring for others. As an office assistant in his suite, I’m almost guaranteed to play a game of fly on the wall. Perching behind a plexiglass window, I silently note when he erupts through the door with milkshakes or chicken sandwiches for everyone at work. I find vegan brownies and blondies waiting on my keyboard, a card for every holiday. His drawers are stocked with goodie bag fillers and fun-shaped erasers, candies and stuffed toys that sing. He routinely offers up university merch, often in gift campaigns for every employee who works under him. He knows them all by first name. He wears bow ties, for crying out loud.

It’s hard to imagine a world in which someone so attentive and outwardly goofy could be considered uncaring or money-hungry. But the plight of leading a university through a politicized pandemic is accepting the harsh reality that it’s impossible to please everyone.

It wasn’t surprising when Old Dominion University closed its doors in March 2020 alongside every other university in the country. Students across the nation anticipated a sun-soaked, restful spring break and were essentially displaced when various institutions prohibited their return. Until the spread of the virus could be studied—and ultimately controlled—universities needed to curate a virtual realm for in-person students to continue their education online. But this hasty transition did not bode well for the majority, and university leaders like Stansberry were caught in the crossfire of political turbulence and excessive safety protocols.

When I immediately ask him to reflect on that initial era of unrest, he pauses to weigh his answer. Though I noted the boldness of his baby yellow quarter-zip upon greeting him, it seems louder when in contrast with the stern expression he now holds. Louder yet is the dawning realization that, as a student, I’d never seen him look so discerning. I gather that this side of him is reserved for highly sensitive topics, those which our professional relationship has never breached.

“We make comments all the time about how this is a technological generation,” he notes, slowly stringing his words together. “Which it is. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that all students have the skills to do virtual learning.” He continues, “[Something] that caught us by surprise was the number of students that didn’t have access to technology at home or in their communities. They were doing papers on their phones.” At this, he holds his cellphone in front of him and demonstrates typing a paper, slightly squinting as if to further convey the difficulty in doing so. The underlying message: no one could anticipate how the pandemic would accentuate the economic disparities between students. And Stansberry is the first to admit that virtual learning simply did not work.

“Our students were not successful. Many didn’t do well academically—not all, but many. And almost every assessment that we’ve done consistently comes back that they’re lonely; they have high anxiety; they’re not meeting people. It can be a very isolating experience for students where that’s not their preferred learning style.”

The university’s inability to meet the direct needs of students while in a remote setting prompted various engagement groups to boost their creativity to the next level, but without drop-ins or “serendipitous moments when a student is walking by,” many programs and clubs were put on hold. And this only scratches the surface of the dilemmas that university leaders like Stansberry were regularly challenged with.

“When you’re having a small group discussion about issues of diversity, equity and inclusion, it’s hard on that Zoom meeting to have an authentic conversation when you’re not in the same room as people.”

Enter: the era of in-person, on-campus mask-wearing. An introduction to vaccines and the political debate over their effectiveness; mask mandates dotting states across the country; the idea that public safety is an infringement upon rights; and those in the eye of the hurricane, fighting tooth and nail to revive campus life no matter the cost. And oh, is there a cost.

When I inquire about the backlash that coincided with re-opening campus and establishing safety protocols, a wave of comfort washes over him; a wall drops, and he takes a breath. He stops fidgeting for the first time since we began. Perhaps because it’s a rare occasion for anyone to ask Don Stansberry, “How do you deal with it all?” He sighs, “Everyone has a better plan. Or they think we don’t care about students, and that it’s all about the money. But we’re actually losing money.”

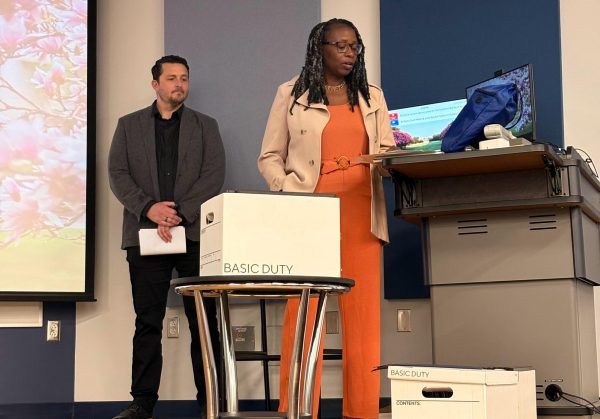

Promptly after the initial emergence of COVID-19, Stansberry teamed up with his fellow unit leaders—including former university president, John R. Broderick—to implement an on-campus testing center in the Jim Jarrett Athletic Administration Building. With a less than 24-hour turnaround on results, the center provides daily COVID-19 testing as well as vaccinations and booster shots, available to all ODU students without need of an appointment. But despite its practicality and general effectiveness in ensuring that students get tested and vaccinated, its maintenance is a hefty investment.

“It’s a machine,” says Stansberry. “There’s a lot of people [involved], and [none of us] have a choice. The same people who should be running the lab samples are trying to run the testing center. We don’t have enough people. And everyone is doing their part, but nobody knows that. They just know ‘I get swabbed and get my results.’” The ache in his voice is similar to that of an overworked parent, shielding their children from the desolation of reality, bearing the brunt of it all. Though, as our conversation trudges along, I think we both conclude that it’s the students who are trapped in the pandemic’s opaque fog. Our university leaders are simply holding up a light—a safe haven, if you will—offering solace where it often feels like none can be found. But this action does not come without criticism.

“[I try] not to let the amount of negativity overwhelm me and remind myself that it’s only been a handful of people who are relentless,” he says. If I hadn’t prodded him to comment on the issue of unpleasant phone calls, he wouldn’t have said anything at all. He just… takes it in stride. “It hasn’t been huge masses, [mostly] parents—or I assume they’re parents, some I don’t even know who they are. But our students have typically had more questions about the why [because] they just want to understand it.”

It’s here that the Stansberry who gifts pink and red stuffed gnomes to his students for Valentine’s Day reemerges into our dialogue. He repeatedly notes that he is not a health professional, but each day he comes into work fully submerged in a healthcare-world and has yet to come up for air. It’s exhausting, and although the burden of guiding ODU is not his alone, he has never experienced the role of vice president outside of COVID-19. It’s unrealistic to expect that his demeanor wouldn’t change when broaching subjects that clearly hit close to home.

“I think you become—as you learn more—you become less scared of what’s happening, and you know where the real risks are. Now we’re saying, ‘This too shall pass.’”

As we wind down, I begin to reflect on the side of Stansberry that I’m uniquely privy to. Behind the plexiglass, I can tally all of the little things that amount to an all-together warmhearted but kooky person. I hear the giggles he shares with his executive assistant; witness the friendly teasing and competitive edge he only reveals while playing white elephant at office holiday parties. But for many students at ODU, Don Stansberry is just another university leader, making decisions for them without any understanding of why. And so I ask, “If you could share a message with students in lieu of the last two years, what would you say?”

He answers without hesitation.

“We are going to provide as many parameters as we can to put safety in place, but at the end of the day you have to be responsible for yourself and make the right choices for you. Our decisions are grounded in keeping everyone healthy and safe, and helping our students to be successful. We always come back to that and ask, ‘what can we do to make that happen.’”

Dana Chesser (She/Her) is an English/Journalism major and second-semester writer for the Mace & Crown. Alongside her role as A&E Editor, she works...

Peg • Feb 9, 2022 at 1:00 pm

Wow. Wonderful glimpse at an amazing man & writer