Hear Their Voices

This article first appeared in the spring 2022 Mace & Crown magazine issue. Included interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Old Dominion University’s College of Art and Letters was proud to host “Hear Their Voices: A Human Trafficking Awareness Event”.

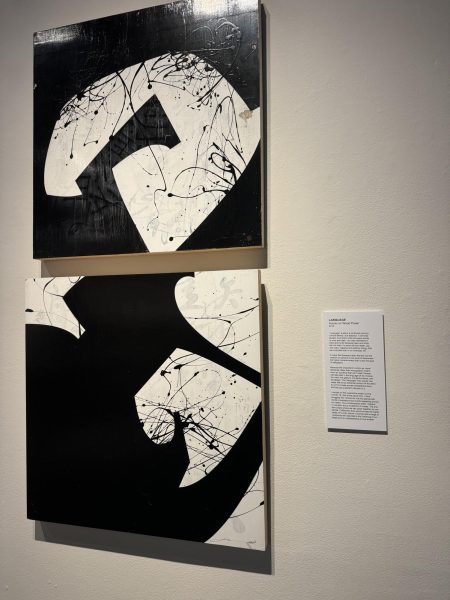

For those in attendance, both in-person and on Zoom, the focal point of the event was a piece of artwork by ODU student Kim McCoy. A wooden frame, about six feet high, graced the center of the spotlights. Clean edges, sanded and varnished till they shone with a dull reflection. Chicken wire composed the sides and top of the frame. Inside, undergarments drenched in an acrylic compound hang from the chicken wire. The acrylic preserves their shape, preventing the wind from rustling them. Religious prayer symbols from a diverse array of cultures dangle on the back wall of the box. Above them, etched into the wood are the words “May All Be Free”. Underneath this phrase hangs crucifixes alongside prayer beads from India. Next to them is a personal piece, a gold figure of Durga, the Hindu warrior woman goddess with eight hands who preserves righteousness. McCoy personally contributed this piece, expressing her desire that the victims be uplifted through her support.

McCoy voiced her desire to do more than just raise awareness.

Her piece grasped the concept of “representing the victims and the perpetrators, with all of us on the outside as those being aware.” This is why the garments, all contributed by people affected by human trafficking, did not move in the wind. The chicken wire, something meant for animals, was there to keep them in, to prevent their movement, to restrict their choice.

Originally an art piece for a class at ODU, McCoy said it turned into something bigger than she had ever imagined. She got her father involved, who was skilled in cabinetry. He fashioned the box, then shipped it to her. After her initial completion of the work, it fell out of the back of her pickup truck on the highway. Landing in the road, it tumbled and was smashed to pieces by oncoming traffic. Incredibly enough, the back of the box remained virtually untouched. The inscription and all of the prayer pieces, numbering at least 20, were unharmed. McCoy, with the help of her father, rebuilt the entire work using the original back part of the box. McCoy remarked on this, saying “it was almost as if to represent all the victims who were being held back, but we didn’t give up”.

“I think it’s really about caring,” said McCoy. “That if we’re made aware of something then we can begin to care for it, and when we care for that we might actually wonder how can I make a difference. I think that’s really important. Also, to any survivors or victims of human trafficking, we want them to know that people are looking out for them and wanting them to be okay. Like the back of the piece says, “May All Be Free” — that is truly my wish.”

Following McCoy’s heartfelt story about the journey of the centerpiece, she was joined on a panel to discuss human trafficking awareness by Dr. Tonya Shell, Dr. Amanda Petersen, and Courtney Pierce. Petersen teaches in the Department of Sociology and Criminal Justice at ODU as an assistant professor. In addition to teaching, she does research on race and gender violence in the U.S. penal system. The final panelist, Courtney Pierce, works as the anti-trafficking outreach and direct service coordinator for Samaritan House, a non-profit in Virginia Beach. The panel addressed a number of misconceptions surrounding human trafficking and provided a number of resources for the community to use in the fight against human trafficking.

First, let’s define what “human trafficking” is. How are force, fraud, and coercion involved?

Courtney Pierce: We use a federal definition, because we’re a federally funded agency. Human trafficking is a crime that involves exploiting a person for commercial sex or labor. Sex trafficking is a commercial sex act induced by force, fraud, or coercion or in which a person is induced to perform a sexual act. It also includes the recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision, or obtaining of a person. Then labor trafficking is the recruitment, harboring, transportation, or provision of a person for labor or services.

What are some common misconceptions about human trafficking?

Dr. Amanda Petersen: There are three main misconceptions I’d love to bring attention to in regards to trafficking. The first misconception is that most trafficked individuals are trafficked by a stranger. In fact, the vast majority of victims and survivors are initially trafficked by a romantic or sexual partner, a family member, a friend, or an acquaintance. This leads to the second main misconception I hear, which is that most trafficked individuals are subject to continual physical force or containment, such as being tied down or locked in a room. While this does happen, in many cases survivors are kept in a relationship with the person who is trafficking them through psychological manipulation and threats. For example, the person who is exploiting the victim might shame them for being in the sex trade, might tell them that no one will love them as much as they do, or might tell the victim that their family and friends will reject them if they know the sex acts they engaged in. People who engage in trafficking might also use threats of violence, actual violence, or threats of reports to law enforcement. Victims who don’t have citizenship status might be told that they will be reported to Homeland Security and be deported.

Lastly, the media often portrays victims and survivors as being white. While there are certainly white individuals who are trafficked, Black, Latina, and Indigenous individuals are multiple times more likely than white individuals. Many scholars and advocates argue that this is because Black, Indigenous, and Latinx girls and women are subject to structural barriers that are correlated with vulnerability to be targeted for trafficking, such as poverty, harsh school discipline practices that push these girls and women out of school, and precarious access to housing. Such an understanding runs counter to the idea that Black girls, for example, are more likely to be trafficked because of some deficit in Black culture or in Black families.

What can we do about human trafficking as a community?

Dr. Amanda Petersen: For those who are interested in volunteering, I’d encourage them to think outside of the box. There are local organizations like Samaritan House that work directly with survivors, but this is just one way of helping to address the problem. Volunteering with Big Brothers, Big Sisters, for example, might not seem like trafficking prevention. However, it introduces an additional caring and attentive adult into the life of a young person which can make all the difference. Other volunteer opportunities such as helping out with an after-school program, helping sort or distribute food at a food bank, or helping immigrant or refugee families get established in their new community are all forms of trafficking prevention.”

Courtney Pierce: What happens is a lot of folks, when they get to Samaritan House, have experienced years and years of childhood trauma and then trafficking is sort of the icing on the cake. A lot of that is because there was no prevention work done within school systems. And the majority of all of our program participants were trafficked by either team members or an intimate partner. So, for example, if there’s a healthy dating relationship program that you can be a part of, that’s a great way to combat trafficking, because the majority of people were trafficked through intimate partner relationships.

Trafficking happens to all types of people. What are some of the risks and social factors that make certain individuals vulnerable?

Dr. Amanda Petersen: Some of the primary risk factors associated with trafficking are poverty, substance use, mental health issues, relocation or migration, family violence, childhood trauma, homelessness, and poor self-esteem. Many adolescents who are trafficked had run away from home or were kicked out of their houses.This is a particular problem for LGBTQ+ individuals who are still too frequently rejected by their families. LGBTQ+ young people are disproportionately represented in the homeless population making them disproportionately vulnerable to commercial sexual exploitation. Additionally, individuals who are engaged in consensual sex work but are doing so because of a substance abuse problem or poverty are at risk for victimization. While these individuals enter the sex trade consensually, they may meet someone who promises them higher pay, more clients, or better clients, but then becomes forced to do sex work they did not consent to. This happens with both young people and adults.

What legislation might we see to combat trafficking in the coming year?

Dr. Amanda Petersen: My biggest hope when it comes to legislation is always that more funds will be allocated to organizations that are directly working to meet the needs of survivors. Additionally, all of us, including our legislators who care about trafficking, need to understand that anti-trafficking legislation is first and foremost legislation that facilitates universal access to basic things like safe housing, a living wage, healthcare, holistic substance abuse recovery programs and quality education. In other words, we must address the social inequalities and problems that put people at risk to be trafficked, or to trafficking someone else, in the first place. Otherwise, all our responses will be reactionary. It often seems like the solution is to direct more money to law enforcement, but this is a problem for several reasons. Many police agencies continue to target and arrest sex workers, meaning victims of trafficking are afraid to have contact with the police. Further, the only real role police can serve is to arrest someone — they can do very little to prevent trafficking, and it is beyond the scope of their work to do anything to meet the ongoing recovery needs of survivors.

How has art brought more of a spotlight to what you do?

Courtney Pierce: Art is paramount for sure. We believe that the anti-violence movement has always really been driven by people who have a creative mind. We think about poets and writers like Bell Hooks, Angela Davis, Jim Jordan and James Baldwin. Then we think of artists, musicians, and actors. I would say that the arts play a huge part in bringing awareness to certain issues in a way that is accessible to our community. Because a part of the arts and writing and music is a part of our ethos as human beings. It’s a beautiful way to connect but it’s also a beautiful way to expose and share things that are not so uncomfortable. Art speaks a thousand words without even saying anything. And so it’s important to have artists that feel deeply connected to issues of oppression and humanity and to really use their art to help speak out.

Human trafficking can be stopped with your help. Please, if you see something, say something.

The National Human Trafficking Hotline is +1 (888) 373-7888.

For those looking to donate, visit https://polarisproject.org/.

Jonathan Fernandes is majoring in English with a focus on creative writing and journalism. At this time, he serves as the news editor for the Mace and...

Elena Harris is a speech pathology major and photography minor graduating in the spring of 2023. Outside of the Mace and Crown, Elena enjoys the ODU experience...